Malcolm X and President's Day

- J.R. Woodward

- Feb 21, 2022

- 7 min read

Malcolm X and George Washington

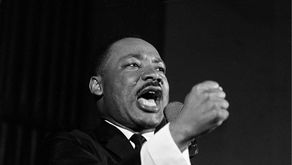

“Distinguished guests, brothers and sisters, ladies and gentlemen, friends and… enemies.”

Today is the 57th anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X, as well as “President’s Day” in America. I found this to be an interesting juxtaposition, so, at the risk of tumbling into didacticism, I wanted to say a little about Malcolm and his impact on my sociological imagination.

The first thing to point out is his name… He was born Malcolm Little, to a mixed-race woman (who was ashamed of her white blood) and an African American man, last name of Little. At some point, Malcolm realized that most African Americans in the United States don’t have “true” last names; their last names came from the slave owner who bought them, and they became his property, and, in terms of nomenclature, his progeny. Upon this realization, Malcolm changed his last name to “X”: unknown.

His mother, Louise, was born in Granada, and his father, Earl, was a Georgia-born Baptist minister who was an ardent follower of Marcus Garvey (of the pan-African movement) and outspoken critic of America’s policies towards people of color. One of eight children, Malcolm was raised in a home that challenged the dominant racist ideology of the day, and his father Earl was killed at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan. He was struck in the back of the head and laid across a streetcar track where he was run over. Consistent with the times, his death was ruled a suicide, so Louise received no life insurance payments. This was the world that produced Malcolm X.

Malcolm eventually turned to a life of petty crime and was arrested and sent to prison in 1946. His real crime, in the eyes of the law, was that he was dating a white woman. He and his closest friend (played by Spike Lee in the biographical movie he produced, “Malcolm X”) were arrested along with their white girlfriends. Both African American men received prison sentences, both white women did not.

It was in prison that Malcolm Little became Malcolm X. At some point he came under the tutelage of John Bembry and started to dabble in The Nation of Islam. Eventually he became a member of the Nation, even though he had no prior religious affiliation. The message he was hearing resonated with him- whites are the devil, and all relationships he had with whites throughout his life seemed to confirm this. At this time, not coincidently, the FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, created a file on him and would continue to follow his movements the rest of his life.

Upon his release from prison in 1952, Malcolm became a transcendent activist and public speaker. He spoke on street corners, at college campuses, coffee shops... At 6’3” and handsome to boot, he attracted crowds with ease… By the early 1960s he was rubbing elbows with Gamal Nasser in Egypt and Fidel Castro in Cuba, but he was also becoming disillusioned with the Nation of Islam and its leader Elijah Muhammed. In my opinion, this period represents a critical shift that provides a deeper understanding of Malcolm X.

Around 1962-1963, Malcolm began a transformation as he left the Nation of Islam. By 1964 he had officially left the Nation, fueled in large part by his pilgrimage to Mecca. While there, he encountered Muslims of all backgrounds, different nationalities, languages, and, importantly, skin color and eye color. He concluded that Elijah Muhammed and the Nation of Islam were too restrictive, and he announced the formation of a new organization called The Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Soon after, Malcolm X was assassinated while preparing to give a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan. Three members of the Nation of Islam were arrested, convicted of murder, and given indeterminate life sentences. Mujahid Abdul Halim admitted to being one of the three shooters, but without naming the actual remaining shooters, declared that his two co-defendants, Muhammad A. Aziz and Khalil Islam were innocent, and in fact, were not even present at the scene. Regardless, all three were convicted.

Halim was released on probation in April of 2010 and lives quietly in New York City. In November of 2021, the convictions of Aziz and Islam were overturned after a District Attorney’s Office report found that the FBI and the New York Police Department had withheld key evidence that, had it been turned over, would likely have led to the men’s acquittal.

I talked to my classes about this news when it happened last fall, and as we discussed it, I realized that most of my students did not know who Malcolm X was. In fact, many had not even heard his name; this was arresting to me because almost everyone my age, sociologist or lay person, knows who Malcolm X was, and it caught my attention that he has fallen by the wayside among the youth of today. The “youth of today” in my orbit at least…

But trying to succinctly summarize him is challenging. Until his break with the Nation, Malcolm espoused views that were incendiary to many. He broke with the mainstream Civil Rights Movement as well, and its leader, Martin Luther King, seeing both as acquiescing to whites. He famously called King’s March on Washington the “farce on Washington”, and said it was “run by whites in front of a statute of a President who has been dead for 100 years and didn’t like us when he was alive”. Well, hard to argue that part…

He also rejected the mainstream Civil Rights Movement’s focus on non-violence, instead stating that African Americans should strive to achieve freedom by ‘any means necessary’. In a speech from December 1964, Malcolm stated:

“Freedom is gotten by ballots or bullets. These are the only two avenues, the only two roads, the only two methods, the only two means- either ballots or bullets. And when you know that, then you are careful how you use the word freedom. As long as you think we are going to sing up on some, you come in and sing. I watch you, those of you who are singing- are you also willing to do some swinging?”

People accused him of promoting violence, but he called it counter violence (or self-defense v masochism). For example, if an African American in the South is trying to exercise their right to vote, and someone uses violence to deny them their constitutional right, then they have the right to use counter-violence to effectuate their rights under the law.

His pilgrimage to Mecca has always been the line in the sand for me. I’ve heard people over the years criticize Malcolm as “racist, anti-white, full of hatred”. And I have always asked those people what they know about pre-Mecca Malcolm and post-Mecca Malcolm.

Many of his critics use quotes from his early years of ministry to discredit him, and they ignore his later work. At a Freedom Democratic Party rally on December 20, 1964, for example, Malcolm made no demarcations along racial lines, as long as the goal was pure: “They’ve always said I’m anti- white, but I’m for anybody who’s for freedom, I’m for anybody who’s for equality. I’m not for anybody who tells me to sit around and wait for mine.”

And let me be clear here, that even though I recognize his post-Mecca work was more inclusive and possibly realistic (after all, maybe we need “all-hands-on deck” to eradicate racism), I have a hard time rejecting much of his pre-Mecca work. Essentially, he was saying: everywhere white Europeans have gone, they have sowed callousness and viciousness. They are certainly not the only folks on the planet who have done such, but it’s a reality that is hard to escape.

I began to delve into Malcolm’s work as a master’s degree student at the University of Alabama, and I read all his speeches and writings. All of them. I remember my mother, who was in her 30s during the Civil Rights Movement, telling me that white folks were afraid of Malcolm, and that told me he was someone to be reckoned with.

My pursuit was aided by Buster Allaway, a Professor of Marketing at Alabama, who’s daughters I taught swim lessons to. A big burly white dude from Texas, he and I played golf together wearing our black baseball caps with the big white “X” emblazoned on the front. We bought them in 1991 after Spike Lee’s movie came out commemorating the 25th anniversary of Malcolm’s death, and we’d tell people at the country club it represented our average score per hole, in Roman Numerals. But in those days, in Alabama, everyone knew what that cap meant, and it was another rhetorical line in the sand…

So how did Malcolm X view George Washington, whose birthday is still the official name of President’s Day? On one hand, he was quick to point out the hypocrisy: “I read in a book where George Washington exchanged a black slave for a keg of molasses. Why, that black man could have been my grandfather- you know what I think of ol’ George Washington.”

On the other, he used the example of George Washington’s violent revolution as justification for a new world order, a sea change of perspective, among those of color. “If George Washington didn’t get independence for this country nonviolently, and you taught me to look upon him as a patriot and a hero, then it’s time for you to realize that I have studied your books well.”

At the end of the day, when we examine the primary movers and shakers of what W.E.B. Dubois predicted would be the “Century of the Color Line”, I believe Malcolm X’s legacy remains integral, at the most fundamental level, to struggles for equality both in the U.S. and abroad. Other than some gendered language, I find it hard to poke holes in his fundamental analysis, which, for me, might be summed up in this statement introducing the secular Organization of Afro-American Unity, in March 1964:

No, I’m not an American. I’m one of 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism. One of the 22 million black people who are the victims of democracy, nothing but disguised hypocrisy. So, I’m not standing here speaking to you as an American, or a patriot, or a flag-saluter, or a flag-waver – no, not I. I’m speaking as a victim of this American system. And I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.

Comments