Health Care as a Human Right

- Feb 17, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 3, 2020

As the 2020 presidential election draws near, the most common talking point among the Democrats rivaling to become their party’s candidate is the issue of health care, specifically the idea of “Medicare for All”. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both support expanding the existing Medicare system to cover the entire population, though their mechanisms to achieve this vary somewhat. The remaining candidates are either against the idea completely, or prefer a more gradual Medicare expansion. To my knowledge, no Republican lawmakers support the expansion of Medicare specifically, nor universal coverage more generally. At the root of the health care debate in the U.S. is the question of whether health care is a ‘right’ of citizenship, like the right to vote or the right to protest, or a ‘privilege’, like driving or retiring. We have historically viewed health care as a privilege, a commodity to be bought and sold in the market. I propose that we would be better served viewing health care as a social service, guaranteed to all our citizens and doled out equitably, consistent with many nations around the world. I feel health care is a fundamental human right for at least three reasons. (For the purposes of this post, I will conflate ‘health care as a human right’ with ‘universal health care coverage’, since countries that see it as a right typically provide universal coverage, and countries that provide universal coverage typically do so because they see it as a right.) First, the Declaration of Independence claims that Americans have “an unalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”. It would seem that life, particularly a healthy one, is imperative in order to enjoy liberty or pursue happiness. Second, the United States has signed onto the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948); we were an original signatory and Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was on the drafting committee. Article 25 states “[E]veryone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself (sic) and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services”. Our courts, however, have never ruled that this document applies to health care in the U.S. Third, the U.S. is one of the only nations in the developed world that does not guarantee health care access to all it’s citizens. Over 120 countries provide this access, and we are the only “developed Western democracy” that does not. One might be tempted to say, “just because other countries are doing it, doesn’t mean it is right for America”. However, when you examine the health status in countries around the world, it is clear that it is. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States ranks 37 out of 191 countries based on overall performance. Our system excels in advanced technology, but lags behind in overall levels of population health, health system responsiveness, extent of health disparities and the distribution of financial burden, among others. When the U.S. is compared to other member nations of the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a group of 36 democratic countries considered ‘developed nations’ who control approximately 62% of the worlds’ Gross Domestic Product, our health care system looks even worse than the WHO data that includes many undeveloped nations. We are in the middle of the pack for life expectancy (approximately 80 years) and self-rated health, but are at or near the bottom in avoidable mortality, infant mortality, population coverage, and financial protection. However, we are at the top in two important categories: health care expenditures per person per year (about $10,000), and health care spending as a percentage of our Gross Domestic Product- we spend approximately 17% compared to the next closest country, Switzerland, which spends around 12%. So, where does this leave us? If nearly every country in the world views Health Care as a human right… And the U.S. is the only developed nation that does not recognize that human right in practice… And our health status is marginal relative to countries that DO view health care as a human right… Then why doesn’t the US view health care as a human right and provide universal care? This is a million-dollar question, complex and convoluted, beyond the scope of a short blog post. Therefore… I’m going to try and answer it anyway, using the sociological perspective. Peter Callero sums up the approach well: “Sociology, as a perspective, as well as an academic discipline, directs our attention away from isolated individuals and towards groups, institutions, and the web of social connections that we call society”. Applying this approach, one would ask what separates the United States from nations that view health care as a human right? First is the “Jeffersonian Ideal” that arose early in the country’s development exhibiting a mistrust of government, particularly a federal government, and celebrating self-sufficiency and individual responsibility. Focusing on the individual, instead of our membership in social groups, reinforces the belief that our lot in life (whether we have health care, high educational attainment, etc.) is due to our own individual efforts within a supposedly meritocratic system, uninfluenced by structural factors. Another potential answer can be found in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, a classic book by German sociologist Max Weber. In simple terms, Weber postulated that the tenets of capitalism slid nicely next to the tenets of Protestantism and Calvinism. If god has predetermined who has been saved, one way to catch a glimpse of your prospects for salvation is to use profit and material success as a sign of god’s favor. So, both the economic and religious narratives in America focused on independence and looking out for self, rather than a focus on the collective good. A final clue comes from French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu and his notion of economic vs. social costs. Too often we separate the two and don’t recognize the impact of the social on the economic. When governments ask sociologists to study health care, or politicians discuss problems with health care, what do they typically want? To make it cheaper. But to base health care debates on ‘cost-savings’ disassociates the economic and the social “because what is social IS economic” according to Bourdieu. “There is nothing which lies outside this enlarged economy”: sadness, joy, the fear of not being able to pay for your children’s medical bills, the pleasure of breathing in clean air, the ability to exercise at night in your neighborhood, all of these things that universal health care could contribute to, pertain to economics. So, a savings in the short term (if such a savings would even exist), will be paid for by the collective in the long term. A healthier population is a happier, more productive one. I will close with a quote from the late senator Edward Kennedy in a letter to Barack Obama a few months before he passed away in 2009: “What we face is above all a moral issue; at stake are not just the details of policy, but fundamental principles of social justice and the character of our country.” I urge you to consider these words in the voting booth this fall.

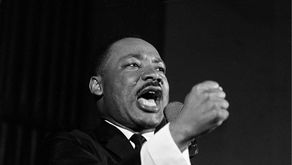

[Cover photo courtesy of David Simonds, with many thanks.]

Comments